Shorter and Sweeter

The issue of immortality, whether spiritual or corporeal, has fascinated human beings for as long as we’ve told stories. The idea of eternal life has been both a motivation for better behavior in this life and a panacea (or a placebo) for all the injustices and oppression we experience. At the same time, everything from Greek myth to contemporary science fiction has raised complicated questions about the downsides of immortality. It’s tempting to see contemporary health technologies which intend to extend human life as medical efforts to attain what has up till now been primarily a religious or science-fictional goal.

But on a planet already reeling under the impact of overpopulation, perhaps it’s time to acknowledge that extending human life indefinitely is as irresponsible as encouraging people to procreate at or above the level of population replacement. It’s short-sighted and selfish. And it’s everywhere.

Research into aging and longevity has seen a significant uptick over the last decade, in terms of both publications and funding. That’s not surprising when one considers the so-called “silver tsunami” – a rapidly aging global population conceived as a kind of natural disaster headed our way, and also as a potential surge in revenue. Aging is variously presented as a disease, as “a critical matter of global economic security,” and as something we have to fight (and if you want to know how, the answer is: “Give us money”).

It’s certainly true that age-related diseases are putting an increasing strain on our medical and social systems. But we’d do well to remember that governments want to lengthen the “health span” and longevity of their citizens not because they love us and want us to be happy, but because increased life expectancy among reasonably healthy individuals adds trillions in economic value every year.

Unsurprisingly, longevity and “health span” are presented in terms of solutionism – as another capitalist competition for more and better years, another techno-fix, another resource we can acquire, something to be measured in terms of bar graphs and pie charts. Researchers talk about predictors of early death. But what exactly is early death? Early compared to what? And who decides?

In popular TED talks on these subjects, we’re told that living to the age of 90 is “optimal,” but the average lifespan in the US is 78. So “we’re leaving 12 good years on the table!” As if lifespan were another boardroom negotiation. As if longevity is something “we” are entitled to as part of our “deal” in life.

It’s worth asking: Who is this “we”? It’s already limited to the human in this case, but this “we” is really an even narrower slice of the planet’s population. The people who “live to be 1000” will not be those who grow up without access to basic healthcare or quality education. They won’t be those who live in food deserts. And they won’t be those who live with the kind of constant, mid-level stressors that typify a hand-to-mouth economic existence.

The “we” is those of us who can afford to develop a “lifestyle,” those who have the luxury of time and the financial resources to “cultivate happiness” – meditation, massages, gym memberships, organic food, vacations, preventive treatments, top medical care – all the things our TED saviors tell us we need to “live better longer.” This view of longevity and healthy aging is another outgrowth of hyper-individualism and late-stage capitalism.

On a planet that can only support so many people, why should the rich and the well educated get to stick around at the expense of both human and non-human others? How would research into health span and longevity change if we widened the scope of our inquiry – not only beyond the small percentage of human beings able to afford current and future anti-aging therapies, but to the planetary community as a whole? What if “health span” was a matter of the health of the planet rather than only the health of human individuals? How might the ethics of answering these questions change if we think of alleviating age-related suffering in these collective rather than individual terms? Since education is (one of) the best predictors of longevity, what if we focused our resources on improving universal access to education rather than pouring money into drug and genetic research?

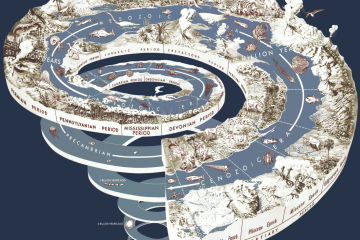

Going further, what if we thought of the optimal length of human life not in terms of individual desires but in terms of both communal and planetary needs? If we think beyond the individual, aging can be seen not as a disease or an economic threat but as part of a communal process, with opportunities for positive change and transformation. That’s what stories about aging and death did for us in the past: they helped us see these changes as opportunities. But now that such mythical-religious language is on the wane, how are we to confront these issues without succumbing to the language of disease, bargaining, and profit?

Mired in our intersectional environmental and population crises, we need new stories to tell – stories that don’t prioritize the human experience over everything else. Max Porter, Cristina Rivera Garza, Richard Powers, and Elvia Wilk are among those telling such stories. Porter and Powers encourage us to think more holistically about landscape and lifespan. Rivera Garza’s work challenges binary divisions and borders, including those that set human beings apart from other beings. Wilk observes that solutionism is problematic primarily because it continues to center the human as the primary concern, the primary actor, and the potential savior. She notes that human beings have never been good at anticipating the collateral damage of our solutions, and we have never been good at simple restraint as an alternative.

We tend to be frightened of change, and death is the biggest one we face. But stories can help us face our fears, and change can also be seen as transformation. We do not need more of the same solutionism. We need a wider purview. We urgently need both research and discourses that help us reconceptualize human aging and death as part of a wider, longer, deeper planetary health span.

#

Alissa Jones Nelson completed her PhD at the Centre for the Study of Religion and Politics at the University of St. Andrews in 2009. In 2011 she began her #alt-ac career, working first as the Acquisitions Editor in Religious Studies at De Gruyter and then as the Senior Editor and Head of the Publishing Department at the Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute. She now works as a freelance writer, editor, and translator, based in Berlin. She is also the Publications Manager for Counterpoint. Learn more about her work here.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 4 September 2019.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

0 Comments