Stags, Stones, and Stakes: A Point/Counterpoint Conversation with Jay Johnston

Point: From Regimes of Mastery to Creative Confusion

Jay Johnston’s new book with the enigmatic title Stag and Stone: Religion, Archaeology and Esoteric Aesthetics is a stunning and elegant piece of scholarship. It carries on musings about the fluid borders between the spiritual and the material that Johnston had presented in her Angels of Desire: Esoteric Bodies, Aesthetics and Ethics, now focusing on ‘troublesome’ objects and places such as speaking stones, landscape amulets, or ‘prehistoric’ cave paintings. Bringing together ancient archaeology, cultural studies, animal studies, aesthetics, and religious studies creates turbulences that are highly productive indeed. For this Counterpoint Conversation, I want to highlight some of the arguments that resonate with themes and topics discussed widely on this blog, and I want to invite Dr. Johnston to be even more explicit about the implications of her considerations for an opening up of the academy to the unknown, the bewildering, and the aesthetic.

Stag and Stone is a powerful contribution to the still emerging discussion about whether the other-than-human world has a life and a will of its own, and how this intersects with human life, knowledge, and perception. An entire technical language has developed around these questions, and today scholars speak of the ‘agency’ of nonhuman animals and of ‘things’; they theorize the ‘vibrant life’ of matter and explore the ‘relationality’ that links human life and communication to the other-than-human world. What seemed to be neatly distinguished in European imagination—the subject and the object, the animate and the inanimate, the material and the spiritual, but also past, present, and future—suddenly collapses into one big hodgepodge of relationships. Finding order in this web of agentic relationships isn’t easy, also because we can’t be sure if the order we see is just a projection of our own limited understanding.

Addressing the field of ‘new materialism,’ Jay Johnston therefore identifies

one of the most challenging issues for New Materialist archaeologies: that of delineating artefact integrity and maintaining an understanding of this integrity within the dynamic ‘ecology of practices.’ How do we recognise the limits of a ‘thing’s’ agency without reintroducing anthropocentric expectations and experience in its dynamism? Is much of this agenda not already premised on the idea that ‘things’—even in their vital form—are inherently available for perception? What if a thing is recalcitrant or invisible? What if we lack the skill to perceive it? How do we acknowledge and represent this inherent ambiguity?” Her solution to this dilemma is “giving up discourses of mastery and cultivating an attitude of not-knowing. (p. 32)

I agree that regimes of mastery are at the bottom of the perilous situation we find ourselves in on this planet today. They materialize in current dealings with nature, with gender, with race, with economic power. They also influence our way of thinking and understanding, i.e. the epistemologies our scientific and cultural systems run on. If we are serious in our attempt to break out of these regimes of mastery, we will need to explore our place in a network of relationships that renders our knowledge vulnerable and dependent on the epistemologies and agencies of others. In Jay Johnston’s words: “An environment that acknowledges other-than-human agencies—even if they cannot be entirely perceived, conceptualised, or known—is an ecology of other-than-human agency. Any such environment must be understood to be radically intersubjective: constituted by agencies invisible, simultaneously localised and dispersed, yet capable of maintaining individuated integrity” (p. 236).

Stag and Stone provides many case studies, most of them from Cornwall and the Scottish Highlands, that explore these ecologies of other-than-human agency, from the Pictish stone known as the Rhynie Man, the fairies at Doon Hill and Fairy Knowe that Robert Kirk described, the Dun Carloway Broch on the Isle of Lewis, and the chambered tomb Maeshowe on Orkney.

The case studies illustrate the need to rethink the way we organize the production of knowledge in academic and cultural settings. The implications can be quite radical and unsettling: “The call of this volume—in all its messy multiplicity—is for bewilderment to be treated within the academy not as a shameful state of ineptitude, a failure of mastery, but as a strategically invited state of creative confusion that opens the subject to the ‘other.’ A place and state where insightful conversations ensue, and the self and multiple ‘others’ transform within the relation” (p. 240).

What I find inspiring—and indeed necessary in the current state of planetary affairs—is how these conclusions combine theoretical insights with academic practices. Some of these implications remain implicit in Stag and Stone. Hence, I want to invite Jay Johnston to tell us a little bit more about her take on that. Concretely, and in terms of ethical-theoretical considerations, I’m curious about the concept of ‘radical alterity’ that Johnston alludes to as a means to navigate anthropocentrism in our relationship with the other-than-human world. In terms of academic practice, I’d love to hear more about the concrete changes in how we ‘do’ science and research in a world that is radically intersubjective.

Counterpoint: Hidden in Plain Sight/Site

By Jay Johnston

I was overwhelmingly humbled to read Kocku von Stuckrad’s engagement with Stag and Stone and remain deeply honored and thankful for his critical engagement with the text. My response aims to dialogue with the crucial points Kocku raises regarding (i) radical alterity in relation to other-than-human agency and (ii) consideration of what a radically intersubjective world means for the practice of science. Both these topics pivot on the term ‘radical.’ To my mind the term denotes a foundational mode of relation. This embraces the term’s etymological heritage, which the Oxford English Dictionary (2000) locates in the Latin, radicalis, pertaining to, or formative of, roots. These roots are a living, flexible anchor upon which relational practice grows. Such relations will support incommensurability without denigration or erasure while at the same time enable its necessarily partial and/or plural recognition. This may all sound rather abstract, but hopefully the following ‘counterpoint’ will help to flesh out its practice. The emergence of other-than-human agencies is gleaned in unexpected places.

Recently I read Raewyn Connell’s assessment of the profoundly damaging effects of neoliberalism on education. Amongst this insightful but disheartening assessment of policy and practice (that continues in new and trickier forms) I encountered an unexpected moment of delight. As Connell implored readers not to collapse into despair she wrote: “As Shakespeare put it, in the direst times, stones have been known to move and trees to speak” (p. 110). While the evocation here appears intended to signal hope for unexpected ruptures to the dominant order, my particular delight was in finding this snip of bewilderment within academic prose. Further, in its positioning as having a value, proffering an opportunity, to subvert the lived dynamics of a restrictive system. Its inclusion shattered the authority of dominant discourse: both that which Connell was deftly deploying in the article and that of the neoliberal education system being assessed. In an astute flick of prose another regime of relations was present.

I argue in Stag and Stone that the active recognition of any such other-than-human agencies in and of themselves, that is, as more than mere anthropomorphic attribution, necessitates relations of radical alterity that are founded on the conscious cultivation of perception. Radical alterity is a philosophical concept of onto-ethical relation developed predominantly in the work of Emmanuel Levinas, Luce Irigaray, and Gilles Deleuze. Reductively defined the concept denotes relations premised upon accepting that the ‘other’ is not by default a reproduction or version of the (ontological) self. Setting aside further philosophical discussion, it suffices in this conversation to note that Stag and Stone extends this relation of radical alterity to be inclusive of other-than-human agencies. In so doing, I emphasize that the question of how this other of radical difference is to be perceived is of crucial ethical importance. Through investigation it appears that many methods were already ‘hidden in plain sight.’

How we perceive matters. Our sensory capacities matter politically, ethically, socially, emotionally, physically. That is, what is within our purview and what we don’t see and the attendant culturally determined yet implicit valuation and ordering of that sensory information. Changing our perceptive capacities has, after all, been key to the ‘mindfulness’ industry which is based in large part upon teaching participants to be more consciously attentive to the world around them: the redirection and ‘elongation’ of the gaze being linked to redirection of action, priority, psycho-physical health, and interpersonal connection (even if the beneficiary is a profit-making company and the ‘self’ narrowly defined).

The recognition of radical alterity in relation to other-than-human agencies necessarily means that worldviews will be continually dynamic—not ‘set in stone’—and that the perceptive experience will utilize and bring to greater apprehension a range of epistemologies and knowledges. This is inclusive of knowledges that academic institutions may struggle to recognize or value, which, for example, disrupt claims to objective disinterest or perceive agency that cannot be verified by empirical science. For example, vernacular histories of stones that dance, or Indigenous traditions that recognize rivers as subjective entities that speak and act. The examples are innumerable. The method in Stag and Stone was to utilize the puzzles posed by selected ambiguous objects as a focal point for drawing together some of the breadth and depth of this discourse and experience. However, it was also to argue that conscious engagement with other-than-human agency, because of its radical alterity, would only ever be partial. Nonetheless, even though this may be the radical root of these relations, it does not diminish the ethical imperative to actively cultivate our own perceptive capabilities.

This does, as Kocku rightly identifies, leave open a line of critique regarding the ‘real world’ effects of the erasure of scientific authority (undermining for example climate change action). Yet, the claims of Stag and Stone do not advocate for the outright denigration of dominant discourses, including those of reason and empirical science. Modern science has for example routinely registered other-than-human agency invisible to humans, the electroreception of the platypus for example. Rather the call has been for a greater dialogue between, and respect for, diverse knowledge systems and their limits. Science itself is plural, contradictory, and dynamic. Philosopher of science Isabelle Stenger has advocated for a “slow science” (2018), which is apposite for this context. This is a science aware of the implicit cultural values its systems advocate and reproduce, which in Stenger’s rendering is deeply situated and partial. Acknowledging partiality allows for the creative, productive practice of ‘not knowing.’ This is not a refusal to engage, but a practice of engagement that allows the quixotic and querulous to simultaneously maintain alterity and be present.

Although Stag and Stone: Religion, Archaeology and Esoteric Aesthetics ‘behaves’ within many of the conventions of an academic text, it has at its core a strategic inadequacy. A recognition that other-than-human agency will forever escape full human comprehension. This undermines the presumption of a cohesive, knowable self and distinguishes bewilderment as an honest, ethical scholarly framework. What this requires of us is serious play.

Jay Johnston, Stag and Stone: Religion, Archaeology and Esoteric Aesthetics. Equinox, 2021. For more information and to order at 25% off quoting the code EQX visit the book page.

#

Kocku von Stuckrad is one of the co-founders and co-directors of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge. As a Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Groningen (Netherlands), he works on the cultural history of religion, science, and philosophy in Europe. A revised English version of his recent German book will be published as A Cultural History of the Soul: Europe and North America from 1870 to the Present by Columbia University Press in November 2021. He lives in Berlin.

Jay Johnston is Associate Professor in the Department of Studies in Religion, University of Sydney. She is a bad birdwatcher and platypus lover. An interdisciplinary scholar her academic work is at the interface of philosophy, arts and religion and is centrally concerned with subtle bodies, the cultivation of perception and multi-species ethic-aesthetic relations.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 28 April 2021.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

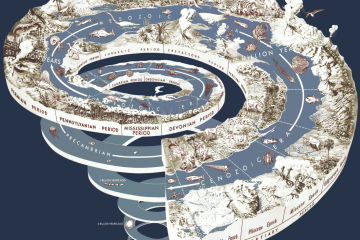

Image credits: Young Stag. Inverkirkaig, Assynt. Digital Photograph. © Jay Johnston 2019 | Callanish Stones, Isle of Lewis. Digital Photograph. © Jay Johnston 2014.

1 Comment

Sea Lions and Seeing the Future – Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge · May 12, 2021 at 12:19 PM

[…] of Sydney religion professor Jay Johnston’s work, explored here on Counterpoint two weeks ago, also looks to the other-than-human, including mysterious knowledge systems like […]