Narrative Warfare and the Noosphere in Steve Bannon’s Populist Revolt

By Boris Shoshitaishvili and Lisa H. Sideris

On July 1, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling that granted Donald Trump considerable immunity from prosecution for his role in the January 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol attack. Rightwing populist victories in Europe flooded the news on the same day as the new ruling.

Partially buried beneath the avalanche of these headlines was a New York Times interview with former Trump strategist Steve Bannon, convicted on contempt charges related to January 6. A few days before beginning his federal prison sentence, Bannon laid out for Times columnist David Brooks his vision of world transformation through MAGA-style movements. In a surprising moment, Bannon suddenly invokes the concept of the noosphere, presenting it as a mass media juggernaut that “is going to so overwhelm evolutionary biology that it will be everything.”

Now just over a century old, the noosphere concept, as Bannon rightly notes, owes its genesis in part to the philosophical and theological musings of Jesuit priest and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Teilhard’s discussions with biogeochemist Vladimir Vernadsky and philosopher Édouard Le Roy in 1920s Paris led the three men to propose a counterpart to the biosphere, lithosphere, and other planetary spheres. The noosphere denotes a newer mindsphere, an enveloping layer of intelligence and technology created through the collective thinking and action of our highly complex species. This superimposition of the noosphere over the biosphere is what Bannon refers to in saying that the noosphere will overwhelm evolutionary biology.

If the noosphere idea, as some scholars argue, sprang from Teilhard and Vernadsky’s deep-seated “revulsion against the horrors of war and strong faith in human potential and science,” its early anti-war trappings mark an intriguing contrast with Bannon’s appropriation of the term. In the key passage from the Times interview, we see Bannon leap quickly across three touchstones—mass media, Teilhard’s noosphere, and the signal importance of narrative—to land back on the theme of warfare that pervades his responses:

I call Trump a Marshall McLuhanesque figure. McLuhan called it, right? He says this mass thing called media, or what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said of the noosphere, is going to so overwhelm evolutionary biology that it will be everything. And Trump understands that. That’s why he watches TV. He understands that to get anything done you have to make the people understand. And so therefore, constantly, we’re in a battle of narrative. Unrestricted narrative warfare. Everything is narrative.

Bannon’s martial emphasis is a departure from the dominant strands of noosphere thought, which have tended in the opposite extreme, with Teilhard and Vernadsky envisioning a harmonious sphere taking shape through human activity.

Beyond this important difference, however, there are common threads between Bannon’s appeal to the noosphere and aspects of the concept’s history. Passages of Teilhard’s writings have elicited charges (and rebuttals to those charges) that his cosmology was “founded upon layers of bias against persons of various ethnic backgrounds” and a bedrock belief in the inequality of the races. For instance, when one encounters a passage in Teilhard such as, “What fundamental attitude . . . should the advancing wing of humanity take to fixed or definitely unprogressive ethnical groups? . . . To what extent should it tolerate, racially or nationally, areas of lesser activity?”, it is easy to hear resonances with far-right ethnonationalist politics like Bannon’s.

Yet, these potential resonances may not be what drew the Trump strategist to the Jesuit priest. Passages like the one quoted above are not common in Teilhard and do not appear in his discussions of the noosphere. Meanwhile in his conversation with Brooks, Bannon himself implicitly relies more on a quasi-Marxist framework of class struggle than one of race or ethnicity. Instead, the clearer connection between Bannon’s and Teilhard’s visions lies in their shared emphasis on media and communication as salvific collective forces and in their conviction that they have identified the direction of history, seen as a global teleology possessing spiritual dimensions.

Bannon first aligns Trump with communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, famous for the aphorism “the medium is the message.” McLuhan’s ideas about the global village and a “seamless web of experience” owe a significant, though largely hidden, debt to Teilhard’s noosphere. But it is in Teilhard’s writings on the noosphere, rather than the global village, that we find a spiritualized appeal that surfaces also, in a profoundly transformed fashion, in Bannon’s words.

Compare how contemporary theologian Ilia Delio, who praises Teilhard’s and McLuhan’s anticipation of the great “paradigm shift” of the 21st century, effected through advances in computer technology and media communications, has characterized the uniquely spiritual dimension of Teilhard’s thought: “We are moving toward a new type of entity, a new world order, a new type of human. This movement is not outside the walls of religion; in Teilhard’s view it is the power of God within.”

A twisted version of these ideas resonates through Bannon’s account of his movement’s power to inspire purpose and meaning in “foot soldiers” engaged in a “hostile takeover of the apparatus.” The MAGA mantra, he tells Brooks, is all about the God within. “It’s a spiritual war. The divine providence works through your agency.” Where Delio concludes with a call for an integrated world of peace and sustainability, Bannon’s central motif is war.

Although Teilhard oriented his thought toward love, and Bannon has fixed on triumph through conflict, their two visions share an overarching narrative structure: an unrestrained gallop toward planetary fulfilment, working through and carrying us along.

For Teilhard, the forming noosphere is a technologized stage of planetary history promising to carry humans into closer contact with each other and the divine, ultimately to what he called, adapting Christian eschatology, the Omega Point. For Bannon, the noosphere-as-mass-media now spreads into a planetary domain in which political figures like Trump, who represent the global populist revolt, can connect with each other and their supporters, overcome international elites, and lead us into “sunlit uplands,” as Bannon announces at the end of the interview, channeling Winston Churchill. Bannon’s worldview appears to blend Teilhardian and Marxian views of history: divinized and with a strong emphasis on enveloping media, like Teilhard’s, yet built around the struggle of social groups, especially socioeconomic classes, like Marx’s.

One challenge for architects of such global teleological narratives is to provide some sense of the motive forces propelling their proposed histories, as well as the nature of the final encompassing result. Yet the narrative’s appeal often comes at the expense of complexity. Teilhard hypothesizes a form of “radial energy” that continues to drive life’s and the planet’s unfolding into a techno-spiritual noosphere. It remains unclear, however, how his vision integrates, and gives proper voice to, the suffering of the human and nonhuman beings hurt by the very unfolding of this grand historical process. After all, the technological and mechanized planetary substrates of the noosphere that Teilhard heralded brought not only new forms of connection and flourishing but new forms of division and death as well, from the atrocities of the world wars Teilhard witnessed to the ongoing depredations of habitats and multispecies life. Giving expression to these legacies of immense suffering would obscure a straightforward story of planetary completion. Suffering, therefore, is largely occluded, or too quickly justified, in Teilhard’s writings on the noosphere.

Bannon’s vision faces a structurally similar challenge: he sees class conflict and grassroots politics proceeding through a vast and overpowering noo-mediascape of dueling narratives. He believes that these planet-scale processes will result in people banding together worldwide in nationalist projects to remake politics and reforge meaning and community. But like Teilhard’s vision, Bannon’s noosphere of competing narratives leaves out its own crucial feature: the need to account for the non-narrative aspects of our political lives.

If one grants Bannon that narrative is an increasingly crucial component of contemporary politics (an idea carefully theorized in David Ronfeldt and John Arquilla’s proposal of noopolitik), and that Trump deftly manipulates this aspect of our intersubjective reality, one should then ask: Can there really be a successful and long-term politics and governance based purely on narrative? Must not the collective mentality of the noosphere that Bannon highlights also engage thoughtfully with the less dynamic aspects of our world, namely, facts and structural truths, which stubbornly resist their narratization into “alternative facts”?

The noosphere concept, like the planet from which it emerges, is multifaceted and evolving. Bannon’s appropriation should not go unchallenged; nor is it grounds for discarding the noosphere idea, especially given our need to find language to engage the planetary dimensions of our species.

Rather, Bannon’s use of the concept—indeed his focus on narrative—provides an opportunity to reflect on the sorts of narratives the noosphere concept has often been subsumed into. From Teilhard to Bannon, the story of a barreling planetary teleology has been a temptation for noospherical thought. In its sweep towards a divinized planet, or divinized politics, the grand narrative risks losing sight of material bodies and their suffering, and, in Bannon’s case, of the materialities of facts themselves.

#

Boris Shoshitaishvili is a USC-Berggruen Fellow with a background in evolutionary biology, comparative literature, and classical studies. His research focuses on interconnections among the Earth sciences, globalization processes, and collective identity. He has published academic and public-facing articles on planetary thought in Anthropocene, The Anthropocene Review, Earth’s Future, and Noema. He earned his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from Stanford University and currently co-leads an interdisciplinary project on Planetary Metaphysics for the Berggruen Institute.

Lisa H. Sideris is a professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, with affiliation in the Religious Studies Department. Her research focuses on the ethical significance of natural processes and how “environmental” values are captured or obscured by narratives and perspectives from religion and the sciences. She is author of Environmental Ethics, Ecological Theology, and Natural Selection (Columbia University Press, 2003) and Consecrating Science: Wonder, Knowledge, and the Natural World (University of California Press, 2017). She has written extensively on Rachel Carson and is co-editor of an interdisciplinary collection of essays titled Rachel Carson: Legacy and Challenge (SUNY 2008). She serves as President of the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge on 9 July 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

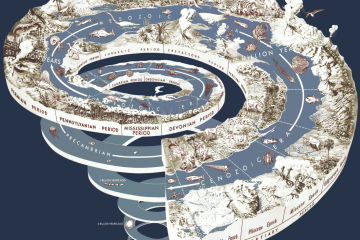

Image credits: An AI generated image of the noosphere, 2024.

1 Comment

#228 Weekend Reads – the sh*t show continues - The Digital Conversationalist · May 24, 2025 at 3:49 PM

[…] aligned to any value system; and explicit appeals to planetary concepts by nationalists like Steve Bannon, who has voiced an attraction to the idea of the “noosphere,” or the planetary sphere of […]