When Does an Individual Human Life Begin? Learning Science from Scientists

When is a science an ethnoscience? When can we say that the observations of nature are being proscribed by the religious framework of the culture? Actually, in the United States, embryology is in danger of becoming an ethnoscience, where religious beliefs trump scientific authenticity and where religion is being proclaimed in the name of science. Senator Rick Scott of Florida wrote in The Wall Street Journal, “Democrats: When Do You Think Life Begins?” Its subtitle reads, “Politicians dodge the question, but the scientific answer is clear: At the moment of conception.” He claims that this view of personhood beginning at conception is “a conclusion grounded in faith and values, but also in science.” Creationists take note: Science and religion can be united.

Senator Scott isn’t alone saying that scientists agree that human life begins at conception. It’s endemic in the Republican Party, but it persists in the general culture as well. When Representative Mike Johnson proposed the Unborn Child Support Act, he told us, “life begins at conception, and this bill is a straightforward first step towards updating our federal laws to reflect that fact.”

Science has not concluded this at all. Where are these politicians getting their “science” from? Certainly these ideas are not coming from the biologists who actually study human embryonic development. I am an embryologist and the author of a major textbook in embryology. While I can say very few things with certainty, one thing I can say with absolute certainty is that there is no consensus among biologists as to when independent human life begins. Different scientists have claimed several different embryonic stages to be the point where personhood might begin. Let’s briefly look at some of these possible stages. When we do, we will see that this idea of zygotic personhood comes from particular Christian views of ensoulment, not from science.

(1) Some biologists claim that personhood begins at fertilization. This view emphasizes the importance of the human genome. In this view of human life, a new individual is created when the genes from two parents combine to form a new genome with its unique properties. Dr. Jerome LeJeune, for instance, states, “Each individual has a very neat beginning, at conception.” But there are numerous scientific criticisms of this view. First, conception is not fertilization. “Conception” is a religious term, not a scientific one. Conception, as the Catholic Encyclopedia tells us, is that time when the soul is infused into the body. This has nothing to do with fertilization. While there are celebrations of the Immaculate Conception, there are never ecclesiastical celebrations (or artistic representations) of the Immaculate Fertilization. Whenever someone starts talking about “conception,” warning flags should appear.

Why, then, is fertilization often confused with conception and ensoulment? One answer comes from sociological studies done by Dorothy Nelkin and Susan Lindee. Analyzing popular literature, they conclude, “DNA has taken on the social and cultural functions of the soul. It is the essential entity—the location of the true self—in the narrative of biological determinism.” As one philosopher has written, “The positive argument for conception as the decisive moment of humanization is that at conception the new being receives the genetic code. It is this genetic information which determines his [sic!] characteristics, which is the biological carrier of the possibility of human wisdom, which makes him a self-evolving being. A being with a human genetic code is man.” And since we get our genome at fertilization, fertilization becomes ensoulment, i.e., conception. Indeed, as Philip Sloane has recently argued, the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v Wade was made largely on the basis of a discredited embryological theory (Preformationism) that supported a particularly Augustinian view of ensoulment.

Genetic determinism is a discredited idea similar to that of preformationism. Our bodies and our behaviors are not prefigured in our genome. Our personalities and our susceptibility to diseases are mostly controlled by our environments. Our genes give us the parameters, while the environment works to create our phenotypes within those limits. Our fate is not only in what genes we possess, but in how we use them. The best trick of our genome is that it allows us to respond to the environment we experience.

DNA is not our essence, it is not our soul. However, our culture continually tells us that it is. Cheesesteaks, we are told, are in the DNA of each Philadelphian, while the sauna is in the DNA of every Finn. No—these items may be in their respective souls, but not in their DNA. When the genomes of numerous Philadelphians and Finns were sequenced, not a cheesesteak nor a sauna was found.

Another critique of fertilization as the point of human personhood comes from fetal mortality. The notion that human embryos are “unborn children” (as was claimed by the Alabama Supreme Court ) is based on the falsehood that once an egg is fertilized, it normally comes to term as an infant. However, most human embryos (probably around 70%) die before birth. Anti-abortion websites often say, “From the first moment of fertilization, human development is a fait accompli, under conditions which we have come to understand and embrace as normal.” This is wishful thinking. It is not science.

In addition, many embryologists claim that whatever personhood may be, it can’t be generated until after day 14. This is when the human embryo undergoes a series of movements (called “gastrulation”) that give cells their identities. Before this time, the embryo can still form more than one individual body—identical twins and triplets. Gastrulation gives the body coherence such that only one infant will form from that embryo. This criterion had been the basis for the “14 Day Rule,” an informal ethical principle that, until 2021, permitted research on human embryos only until the time of gastrulation.

(2) There are places other than fertilization that biologists have claimed as a reasonable origin of personhood. One such view is that personhood begins upon the acquisition of the human EEG (electroencephalogram) pattern around weeks 26–28. Embryologist and ethicist Michael Flower, for instance, concludes, “it is probably not until after 28 weeks of gestation that the fetal human attains a level of neocortex-mediated complexity sufficient to enable those sentient capacities the presence of which might lead us to predicate personhood of a sort we attribute to full-term newborns.” This “neurological” perspective gives symmetry to discussions of life and death: If the loss of the human EEG pattern determines the end of personhood (death; even though the heart may still be beating), then the acquisition of the human EEG pattern should be considered as the point when human personhood begins. This period of neocortex organization is also the time at which the neural receptors in the skin become connected to the brain, allowing the perception of pain. If one considers the perception of pain or rational consciousness to define a human individual (as in the philosophies of St. Aquinas, St. Augustine, Descartes, and Locke), this is a legitimate view of the starting point of a person’s life.

(3) Another prominent position is that personhood begins at or around birth. Physiological personhood occurs when the fetus becomes a baby. Birth is not merely a move from one environment to another; it is a fraught passage wherein the fetus is actively transformed into an infant. While in the womb, the lungs, the last organs to form, did not have to function. The fetus received oxygen from its mother’s blood vessels in the placenta. Upon birth, the baby must breathe as soon as its connection to the placenta is cut. The baby’s first breath of air alters gene expression in its heart, lungs, and brain. The first breath changes the anatomy of the heart, causing cellular tissues to separate the left and right sides of the heart. This alters the blood circulation such that it gets pumped specifically to the lungs for oxygenation. (Billboards may say that a fetal heartbeat begins during the first month of development; but that is a ripple at the bottom of the heart. The month-old heart neither pumps blood, nor has it completed forming its chambers.) That first breath of air also changes the gene expression of the lungs, creating the pathways by which amniotic fluid is absorbed by lymph vessels so that respiration can occur. And last, the first breath changes gene expression in the brain, activating those neural pathways that control the diaphragm and rib muscles so that we can breathe without being conscious of doing so.

(4) Last, many scientists feel that personhood isn’t a scientific category. For many (if not most) biologists, the question of when an embryo becomes a “person” isn’t a scientific question. Personhood is defined socially, not biologically. The concept of who is a person has differed in the western world from time to time. (Indeed, in the Bible, a fetus does not have the rights of a newborn.) Thus, to many biologists, personhood is an issue decided on emotions, upbringing, and politics, and should not be confused with science.

So I can say with absolute certainty that there is no consensus among biologists that independent human life begins at fertilization. Those, who, like Senator Scott, say that such a consensus exists are stating a political or theological opinion, not a scientific fact. Embryology is best learned from scientists, not from politicians.

#

Scott F. Gilbert is the Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology (emeritus) at Swarthmore College, where he has taught developmental genetics, embryology, and the history and critiques of biology. He is also a Finland Distinguished Professor (emeritus) at the University of Helsinki. He has authored and co-authored several embryological textbooks, including Developmental Biology (now in its 13th edition), Bioethics and the New Embryology, and Fear, Wonder, and Science in the Age of Reproductive Biotechnology. He has presented lectures on embryology and personhood at numerous scientific and theological conferences, including a meeting for Planned Parenthood and colloquia in the Vatican.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 29 October 2024.” The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

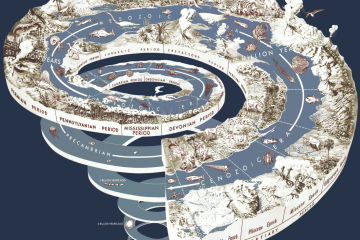

Photo credits: Drawn by Michael Barresi. From Barresi, M. J. and Gilbert, S. F., Developmental Biology (13th ed., 2023) Oxford, University Press.

0 Comments