Circling the Elephant: Why Difference Matters

Recently, my wife and I dared to enter an old local haunt in her hometown, Big Bad John’s, a bar in Victoria, BC. With bras on the ceiling and peanut shells on the floor— it hardly strikes you as a setting for profound religious reflection. And yet, when I confessed to a gregarious stranger that I teach comparative theology, specifically Hindu-Christian and Buddhist-Christian Dialogue, he said something I hear all too often: “Oh, wow, that must make for conflict. It’s too bad that people don’t see just how similar the religions are, how much they have in common.”

To be honest, I never quite know how to respond or even whether to respond. Inside a bar or elsewhere, the sentiment is well meant, and interreligious amity is a worthy goal. But letting such statements slide is becoming unpalatable. After all, I’ve spent decades studying Hindu and Buddhist traditions, learning Sanskrit, traveling to India, and reading and studying with gurus and lamas. I didn’t undertake such laborious learning only to affirm that other faiths are basically up to the same thing. I mean why bother with all that work—only to conclude that there’s nothing new to learn?

But just how to respond? On this occasion, a mantra popped into mind. Maybe it was the Kahlua cocktail talking. I quipped to my new acquaintance, “Similarity makes conversation possible; difference makes it interesting.” I’d word that a bit differently now. Similarity makes conversation possible; difference makes it worthwhile. My mantra made an impression but failed to persuade. My conversation partner remained captive to the conviction that religious difference leads inevitably to conflict. Still, the mantra did create a momentary opening; it interrupted the impulse to celebrate sameness at the expense of difference.

Why should difference matter? The various religions often do have important resonances. Commitment to the dignity of one’s neighbor, hospitality, some version of the Golden Rule, and the call to love and compassion—these are the genuine similarities that make conversation and collaboration possible. But they are insufficient to make conversation worthwhile.

Consider, an increasingly common phenomenon in the West, something that has long been common in the East: multiple religious participation. Increasingly, many Christians and others take up the practices of other religions. Sometimes this happens even inside churches. People take up Eucharist upstairs and yoga downstairs. Others are so serious about their commitments that they become Double Belongers. These are not, say Christians, who are also nightstand Buddhists who do a little meditation. On the contrary, there are JewBus, Jewish Buddhists, Buddhist-Christians, and others who have formally undertaken initiation in a tradition other than the one they were born into but without forsaking their home tradition. For them, taking on another tradition is neither conversion nor rejection but supplementation.

What’s noteworthy about this phenomenon—one that requires a great deal more study—is that that few Double Belongers believe they are up to the same thing when they participate in the Eucharist and practice yoga. They engage a different tradition to meet distinct needs and interests. Difference matters. Otherwise, why waste time engaging in painstaking study, practice, and discipline that merely repeats what you were already doing?

So just what are Double Belongers up to? Answering this question requires turning to a very old Indian allegory told by Buddhists, Jains, Hindus, and others, the allegory of the elephant and the blind men. The allegory is problematic in many ways, not least because it makes the blind look foolish. John Hull, theologian of blindness, argues that tactile learners are too patient and careful to jump to premature conclusions. The blind cannot afford to be hasty. But, putting that issue to the side for a moment, let’s return to the story.

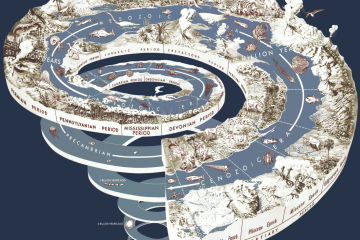

I needn’t retell it here in detail because most are acquainted with it. Several blind men stand around the elephant. Each insists that he knows what this thing called “elephant” is. The elephant is a tree trunk says the one who grabs the leg. The elephant is a spear says the one who grasps the tusk. The elephant is a rope says the one who grabs hold of the tail. They begin to quarrel until a sighted passerby comes along and sorts them out.

The interesting point of the story is that, although there is just one elephant present, each blind man has learned something different about it, something true. The elephant really is like a giant fan to the man who has grasped the elephant’s ear. Each is right about what he affirms but wrong about what he denies. Difference need not have lead to conflict; complementarity—but not sameness–would have emerged if they had taken the time to listen longer.

My hypothesis is that persons who take up the practices of other traditions are pachyderm perambulators; they do the work of walking around to a side of the elephant other than their own. They do not aspire to be all-knowing sighted observers. When it comes to the mystery of the Infinite, no one is all-knowing. All know only in part, and if we shall ever know in full, it will be only after we’ve shuffled off this mortal coil.

Rather than rest satisfied with what they already know, some are called to make a holy pilgrimage to other religious terrain, not because they are dissatisfied with life at home but because they feel that certain dimensions of the divine life may be better accessed there—even if complete, perfect knowledge is unattainable. There are things you can learn only by meditating that cannot be learned at the Eucharistic table—and vice versa. Each tradition grants access to another side of the elephant. Hence, the desire to circle the elephant.

Similarity makes the journey possible; difference makes the journey worthwhile, a truth that holds both inside your darkened local beer joint as well as around brightly lit interfaith dialogue tables.

#

John J. Thatamanil is Associate Professor of Theology and World Religions at Union Theological Seminary. He is the author of The Immanent Divine: God, Creation, and the Human Predicament and the forthcoming book, Circling the Elephant: Constructive Theology through Interreligious Learning. He teaches courses on comparative theology, theologies of religions as well as a course on Gandhi and King. He is a past-President of the North American Paul Tillich Society and the founding chair of the American Academy of Religion’s Theological Education Committee. His Op-Eds have appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and a variety of sites online.

This Counterpoint blog post may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge on 29 Jan 2019.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

1 Comment

Anita Coleman · January 14, 2021 at 11:10 PM

Lovely. My first reaction would have been, hmm, conflict can bring about good – remember Lederach and conflict transformation? And, don’t we have some great biblical examples as well, e.g. St. Paul? Your answer was definitely tactful and better though :). I’ve come to this area of study by way of personal friendships and books by Wayne Teasdale and Fr. Bede Griffiths who call it interspirituality. I guess the Pachyderm Perambulators, Double Belongers – fantastic descriptors – fit here. Slowly going through your book and looking forward to finding more answers there as well. Thank you!