“The Journey of Pachamama” – Dark Green Christianity in West Germany During the 1980s

By Maria Schubert and Simon Wiesgickl

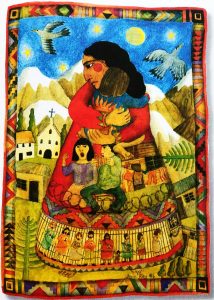

In 1989, the German theologian Bärbel von Wartenberg-Potter wrote a small book with the title “The Journey of Pachamama.” In her book, she shared her insights from her encounters with the spiritual traditions of the First Nations: Resistance for the sake of life is sacred. Everything is connected. The future of the church can be found in embracing Mother Earth.

Those ideas resemble the core elements of what Bron Taylor defines as “Dark Green Religion” (DGR).

DGR scholars have so far paid little attention to developments within Christianity. The latter often serves as a counterpoint to the analysis of Indigenous nature religions. In contrast, we want to show how DGR influenced the Christian tradition. Bron Taylor’s concept is helpful to illustrate paradigm shifts within theological thinking and religious practices between the late 1970s and 1989 in West German Catholicism and Protestantism.

In Catholicism, theologians, clergy, and intellectuals started to engage with the environmental question in the early 1970s (see here). Anthropocentric approaches, which emphasized Christian responsibility of stewardship toward God’s creation, were at the forefront of the discussion. However, the widespread reception of liberation theology and liberation movements in German Catholicism promoted new ways of thinking about the relationship between nature and human life. In the light of environmental issues, the relationship between Indigenous groups and nature, who seemed to live much more in harmony with the earth, received increased attention.

One example of this development is a vinyl record from 1978 published by a group of young Catholic church musicians with the title “Seattle,” named after the leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples Chief Seattle (around 1786–1866).

Chief Seattle contrasted Indigenous holistic views of life and the sacredness of nature to the Christian religion of the settlers. However controversial the origin and authenticity of the text may be, it was discussed intensively in West Germany in the 1970s in the light of the emerging environmental debate. Many Catholics did not see this as incompatible with their own faith, but rather drew inspiration from Indigenous concepts of nature for their own Catholic religious practice. It also inspired Christians to (re)discover traditions in their own religion that showed a different view of non-human life than the prevailing anthropocentrism.

The church musicians used Chief Seattle’s holistic view on human and non-human life to promote a new spiritual relationship to interconnected life on earth. The musicians turned parts of his speech into several songs. The most popular was a canon containing of the phrase: “Every part of this earth is sacred to my people.” It became an earworm at the Catholic Church Congress (Katholischer Kirchentag) in Düsseldorf in 1982.

This is just one example of a significant shift that took place at the Catholic grassroots level and is noticeable in many songs, prayers, and spiritual reflections that were published in the 1980s. Environmental protection is not only described as an act of stewardship toward God’s creation, but creation is perceived in itself as sacred because of God’s presence within nature.

On 8 June 1985, many prominent speakers, singers, theologians, and artists from Germany and the whole world joined hands at a podium at the Deutscher Evangelischer Kirchentag in Düsseldorf. Their goal: to promote a world gathering of churches for the promulgation of world peace. The meeting was a major public event that attracted a lot of attention thanks to prominent participants such as the famous singer Konstantin Wecker and the highly regarded scholar, activist, and writer Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker.

The overall theme of the Church assembly was taken from Psalm 24: “The Earth is the Lord’s.” Hence, ecological awareness was a pressing topic in song workshops, biblical meditations, and political discussions. One of the most popular singers and composers of the Kirchentag-movement, Fritz Baltruweit, exemplified the ecological thinking in a foreword to the song book of the 1985 Kirchentag. He describes a discussion about this question in a confirmation class:

“The earth is the Lord’s, so we humans are tenants on the earth,” answered a confirmation student in response to a question. We liked this metaphor of people as tenants on the earth during our confirmation class. It helps us to understand the world as one household of all people, where we live together as brothers and sisters of one family. (1985, 5)

This songbook is a collection of songs, stories, and prayers from Christians and Indigenous people from all over the globe. It helped to bring home the message of the Kirchentag to many congregations in West Germany and gave birth to songs, which are still sung in many churches today. Apart from that, it shows how ecological ideas from other religions and cultures flowed into the West German church during that time. Very striking is a story allegedly told from girls and boys of the First Nations, which is mixed with a prayer, directly taken from the Vancouver liturgy book. This bricolage of different world views and ontologies illustrates the degree to which grassroots groups paved the way to what can be interpreted as Dark Green Religion.

DGR’s global concept and its affinities with shared histories challenge readings of church history that focus on the nation-state and Western Christianity alone. It may open opportunities for interdisciplinary and international projects that will take church history out of its (sometimes) institutional isolation in the German-speaking realm. In addition, further historical readings and more detailed case studies of ecological thinking and practices in Christianity might sharpen the clarity and enrich the analytical strength of the concept of Dark Green Religion.

#

Maria Schubert is a historian and postdoctoral researcher at the Ruhr-University Bochum. She is currently working on a DFG-project titled “Catholicism in the 1970s and 1980s in West Germany and the Green Party.” Her areas of expertise are modern German history (both GDR and FRG), environmental history, history of Christianity, and U.S. history of the 20th century with a focus on the history of the Black Freedom Struggle.

Simon Wiesgickl is Assistant Professor for Religious Studies and Intercultural Theology at Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg. He is also an ordained minister of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria. He has been writing about German Colonialism and Theology and currently researches the connection of human people and other-than-human people with a postcolonial perspective in the study of religion.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge on 3 September 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

Image credits: Bärbel von Wartenberg-Potter, Die Reise der Pachamama. Eine theologische Erzählung, Stuttgart: Herder, 1989, 24. Used with kind permission of Verlag Herder GmbH, Freiburg i. Breisgau.

0 Comments